It’s Time to Retire Introversion and Extroversion

Take the Myers-Briggs Type Inventory (or any of its innumerable offshoots) and the very first label you’ll be assigned is an I or E for introvert or extrovert. That I or E is also the one member of the MBTI’s four-letter designation most folks remember.

Which is unfortunate, because there’s no such thing as an introvert or extrovert.

In fact, you’ve got better odds of stumbling into a living, breathing Sasquatch (aka Bigfoot) than a human extrovert or introvert.

Here’s why these labels are problematic, and why it matters.

It’s Not My Type

Problem #1: Scientific studies of human personality can’t find introverts or extroverts (just like Bigfoot). Primarily because they don’t exist. (Probably like Bigfoot.)

A century ago Carl Jung claimed that introversion and its opposite, extroversion, represented one of four personality types that every human possesses to one degree or another.

Not so long after, the Myers-Briggs’ mother-daughter team took things farther by maintaining that people were one OR the other. No either-or, no shades of gray. Even Jung knew this was an impossibility, stating that anyone who was completely introverted or extroverted would end up in a lunatic asylum.

But that didn’t stop Myers-Briggs which, absent any legitimate scientific competition at the time, grabbed hold of the public imagination and started labeling millions as pure introverts and extroverts.

“I wouldn’t trust Myers-Briggs to tell me any more about my personality than I would trust my horoscope,” says Katherine Rogers, PhD.

And while it might be convenient to run with a single label, it ultimately creates serious challenges for people genuinely eager to understand themselves.

So that’s problem #1.

What We’re Really Measuring

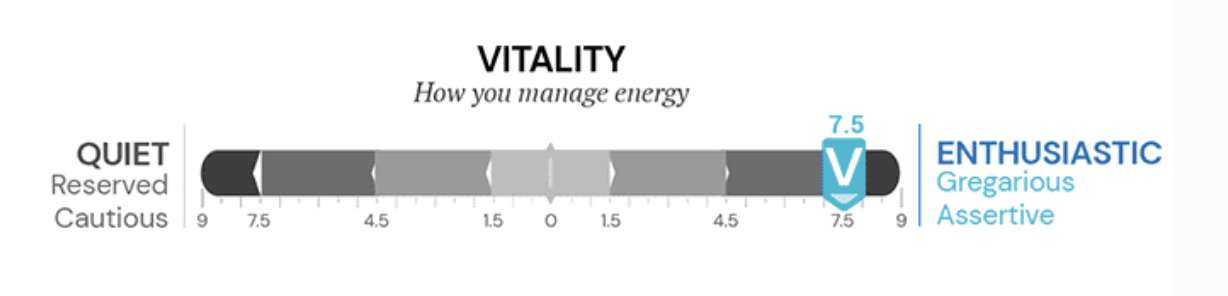

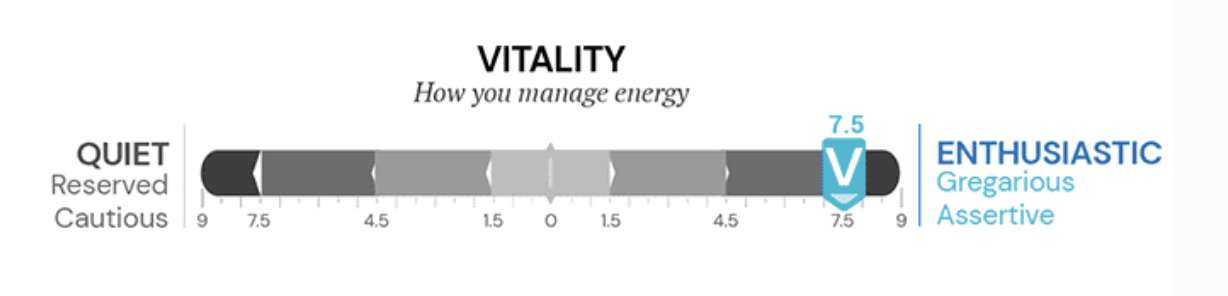

The second problem is that it introversion and extroversion fails to measure or explain what they’re purportedly alluding to: energy management. Meaning that as natural energetic systems, humans are unique in the ways they generate, maintain, and restore their energy levels.

This is critically important, because what charges one person’s battery may drain her counterpart’s; what overwhelms one person stimulates another. And so on. This energy balance can wreak havoc at home (in relationships, raising children, etc.) and at work (ill-suited roles and responsibilities, team construction, etc.).

Traditional Big 5 science calls this trait ‘Extraversion’ (oops!) while we at Lucidata call it Vitality, because language matters and the language we use is more in line with energy management.

For example, a high-octane, outgoing saleswoman who closes a big contract may opt for a solitary hike in the woods with her dog over a noisy celebratory happy hour. And the contemplative seminary student who spend huge stretches of his week in silence, prayer, and meditation may become the life of the dinner party.

This is why we measure the degree to which such ‘facets’ or sub-traits (the building blocks of the Big 5) play a role in someone’s personality. It provides a far more accurate picture.

So that’s problem #2.

People are Verbs, Not Nouns

The final problem with introversion and extroversion is that as nouns, these labels treat people as static things rather than the dynamic states of being they actually are.

Or as Arnie Kozak, PhD, so wonderfully puts it: “Even for those of us farther out on the continuum, where introversion predominates in a much more pervasive way, there is still no such thing as an introvert. Thing implies a noun. Introverts and extroverts alike are not nouns, but verbs. Humans are always in the process of becoming; our thingness is an illusion.”

So the next time someone claims to be introverted or extroverted, remind them that not only do those labels not exist, they keep that person trapped in an inaccurate and limiting mindset.

It’s Time to Retire Introversion and Extroversion

Take the Myers-Briggs Type Inventory (or any of its innumerable offshoots) and the very first label you’ll be assigned is an I or E for introvert or extrovert. That I or E is also the one member of the MBTI’s four-letter designation most folks remember.

Which is unfortunate, because there’s no such thing as an introvert or extrovert.

In fact, you’ve got better odds of stumbling into a living, breathing Sasquatch (aka Bigfoot) than a human extrovert or introvert.

Here’s why these labels are problematic, and why it matters.

It’s Not My Type

Problem #1: Scientific studies of human personality can’t find introverts or extroverts (just like Bigfoot). Primarily because they don’t exist. (Probably like Bigfoot.)

A century ago Carl Jung claimed that introversion and its opposite, extroversion, represented one of four personality types that every human possesses to one degree or another.

Not so long after, the Myers-Briggs’ mother-daughter team took things farther by maintaining that people were one OR the other. No either-or, no shades of gray. Even Jung knew this was an impossibility, stating that anyone who was completely introverted or extroverted would end up in a lunatic asylum.

But that didn’t stop Myers-Briggs which, absent any legitimate scientific competition at the time, grabbed hold of the public imagination and started labeling millions as pure introverts and extroverts.

“I wouldn’t trust Myers-Briggs to tell me any more about my personality than I would trust my horoscope,” says Katherine Rogers, PhD.

And while it might be convenient to run with a single label, it ultimately creates serious challenges for people genuinely eager to understand themselves.

So that’s problem #1.

What We’re Really Measuring

The second problem is that it introversion and extroversion fails to measure or explain what they’re purportedly alluding to: energy management. Meaning that as natural energetic systems, humans are unique in the ways they generate, maintain, and restore their energy levels.

This is critically important, because what charges one person’s battery may drain her counterpart’s; what overwhelms one person stimulates another. And so on. This energy balance can wreak havoc at home (in relationships, raising children, etc.) and at work (ill-suited roles and responsibilities, team construction, etc.).

Traditional Big 5 science calls this trait ‘Extraversion’ (oops!) while we at Lucidata call it Vitality, because language matters and the language we use is more in line with energy management.

For example, a high-octane, outgoing saleswoman who closes a big contract may opt for a solitary hike in the woods with her dog over a noisy celebratory happy hour. And the contemplative seminary student who spend huge stretches of his week in silence, prayer, and meditation may become the life of the dinner party.

This is why we measure the degree to which such ‘facets’ or sub-traits (the building blocks of the Big 5) play a role in someone’s personality. It provides a far more accurate picture.

So that’s problem #2.

People are Verbs, Not Nouns

The final problem with introversion and extroversion is that as nouns, these labels treat people as static things rather than the dynamic states of being they actually are.

Or as Arnie Kozak, PhD, so wonderfully puts it: “Even for those of us farther out on the continuum, where introversion predominates in a much more pervasive way, there is still no such thing as an introvert. Thing implies a noun. Introverts and extroverts alike are not nouns, but verbs. Humans are always in the process of becoming; our thingness is an illusion.”

So the next time someone claims to be introverted or extroverted, remind them that not only do those labels not exist, they keep that person trapped in an inaccurate and limiting mindset.